People who we love use ecstasy, and we want them to live.

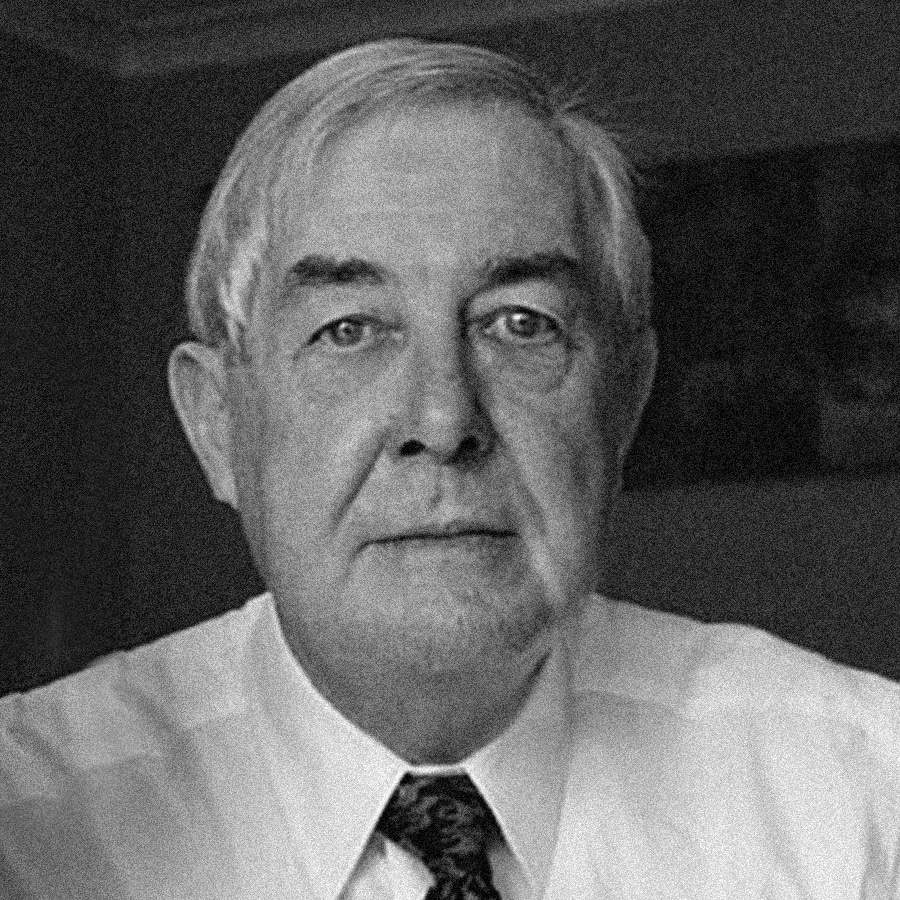

Time’s up Tony Wood

Will Tregoning

2.8.15

It’s a funny feeling when you’re in a club and you realise your friends have disappeared. It was 1998 and I was nineteen. One of them had an anxiety condition, a benzo addiction and a habit of wigging out on ecstasy. It didn’t take me long to join the dots.

I went outside to find a phone and dialled the only mobile we had. It was off. I found out later they were at the hospital and phones were not allowed.

This isn’t a tragic story. No-one died. What I remember is standing beside the phone booth, telling someone else from the club what had happened. ‘Anna Wood’ he said, and laughed. It was meant to be reassuring – as in, ‘that’s never going to happen’. I wasn’t reassured.

Anna Wood was a constant presence in my teens and early 20s. In 1995 she died of overhydration after consuming ecstasy at a rave in Sydney. I was in year 10. She grew up and went to school not far from me.

These were the last days of that era of the Sydney rave scene. On the bus to school one day a friend lent me his headphones to listen to a hard house mix by a DJ called Scooter. When the bell rang for class I was still listening, staring into space and thinking – holy shit, there is another world.

By the time I was 18, dance music and clubs were a big part of my life, and ecstasy was a part of that too. Throughout my early drug-taking years Anna Wood’s story was a constant message: that taking illegal drugs was dangerous, rebellious and cool.

A person born in 1995 would be 20 this year – just entering the decade when ecstasy consumption in Australia peaks. About one in five Australians in their 20s have tried ecstasy, and are willing to admit to it in the government’s triennial survey. (And despite the stereotypes of drug use and failure, wealthier kids who go to university are the ones most likely to use an illegal drug.)

For people my age, Anna’s story was almost universally known and widely discussed, and was the subject of a book that her parents co-wrote. I’ve found that people in their 20s now usually don’t know who Anna was. When her father Tony Wood told Anna’s story during JJJ Hack’s TV show on drugs last week, the younger people responded as if they were hearing the story for the first time.

Watching the show I was reminded again that it’s a tragedy that Tony and Angela Wood’s daughter died. For what they experienced I am, as a parent, sympathetic in a way that’s difficult to express in words.

When Tony tells Anna’s story, it reminds us of what is at stake: the lives of people we love.

But Tony has used Anna’s story to create his own very different but also tragic story. It’s a story of good intentions, but not virtue. Since his daughter died, he’s campaigned for zero-tolerance and for ‘real’ war on drugs. In his grief and in the tragedy of his story, he has become influential and untouchable. He has opposed harm minimisation, claiming it is some kind of conspiracy whose real purpose is to promote drug use. For Tony, the only message is abstinence.

The solutions that Tony proposes are no solutions at all. ‘Just say no’ has manifestly failed to prevent drug use because it doesn’t make sense. Even more troubling is that Tony has promoted an approach that maximises the harm that young people experience from using drugs. He’s helped build a world for my own kids and millions like them that’s more dangerous than it needs to be. A world where more deaths like Anna’s are more likely, not less.

Abstinence is a good message. If it’s the only message, that’s a problem. We live in a world where people use ecstasy. We can and should keep telling compelling stories to young people about why they should not use ecstasy. We also need to respond to the reality that people are using this drug.

There is too much at stake to allow people like Tony Woods to determine how we respond to the reality of illicit drug use. Against his emotion and instinct, we have science and science shows that harm reduction works. It’s also the moral thing to do. People who we love use ecstasy, and we want them to live.

Sign up

Sign up for movement news and opportunities to get involved

We are building a movement to make drug use legal and safe in Australia so that everyone has a better chance to lead a healthy and happy life.